Letter from Seoul - 3

Reminiscences

When I was 10-years-old, my mother arranged for me to attend a special two-week summer camp session for kids who were either deaf or blind. She had attended the same camp at about the same age in the late 1930s. Located north of St. Louis near Hannibal – where Samuel Clemens came of age, there was the easy sense that Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn were just around the corner.

Those of us who had no issues with our hearing or eyesight were screened to make certain we had the appropriate character for the upcoming experience – though I have no idea what that process involved. All that matters is that the two-week experience in the summer of 1962 has remained with me all these years.

The camp had a Sherwood Forest motif, with four separate villages, all based on Robin Hood references. There were eight of us in a cabin with bunk beds, four fellows without any visual or hearing issues, and two who were blind and two who were deaf. It was a remarkable experience.

Children – and we were still children at that point, have not yet been burdened with the discontents of civilization, as Freud describes it, and so there is still a raw honesty that adults usually avoid as life goes on. So we all asked the obvious questions: Were you born this way? How do you know when people approach you? How do you do this or that? And the answers were as varied as you can imagine.

And once all that was settled, we bonded wonderfully over the next two weeks and went swimming and hiking, and were just a regular group of 10-year-old boys at summer camp.

It was at this point that I started writing letters home every other day, which was the beginning of my awareness that I would do what I have done all my life … what I’m doing right now. I’m an inveterate correspondent, a reporter, a journalist.

Some of the fellows with hearing issues attended St. Joseph’s School for the Deaf, a boarding school in St. Louis.

Many years later, when I was a journalist during my Oklahoma period, I worked with Carl Coates who was in the layout department. In that bygone era, there was a need for a few people to literally make up the pages of the newspaper by hand. Once the copy and photos were in place – and allegedly double-checked by the sports editor or education editor in the newsroom, off it went to the pressroom – and the full newspaper came off the presses by 1:30 p.m.

Carl Coates was deaf and had attended the St. Joseph’s Academy in St. Louis as a boarding student. This is where he met his wife, Esther.

By the time I met Carl, he and his wife had raised two sons – neither of whom were deaf. They were well educated, and married with children of their own. Yet at the beginning of Carl’s marriage, the State of Oklahoma made attempts to remove their children and place them with foster parents – or put them up for adoption. Obviously, this did not happen, but the state’s argument was how would deaf parents know when their child or children were in distress? And how could deaf parents initiate language acquisition?

As life is often a matter of how badly you want to achieve your goals, Carl and Esther proved they were not only good parents, they were fine role models.

For a time, the newspaper staff would gather once a month in the lunch room to celebrate everyone’s birthday for that period. Before we had a slice of cake, Carl sang “happy birthday” for the celebrants and it was absolutely charming.

The benefit of working at small town newspapers was that the term journal in journalism really did apply. Every issue was really a journal of the community. In April, 1978, I packed everything I owned into a classic Blue VW – to include a luggage rack on top, and headed to Glendive in Eastern Montana – near the North Dakota border. The town had a population of 7,000 people. I might as well have landed on the moon. But it was long overdue for me to stop prolonging my adolescence. By the time I concluded my career in Ponca City, I had at least reached a town of 30,000 people – with several other newspapers in between, primarily in Montana.

Ponca City is named for a Native American tribe, as so many place names in the U.S. reflect past history. People forget that New York City started as New Amsterdam, and references like Broadway, Brooklyn, Greenwich Village, Harlem, Long Island, Wall Street and Yonkers are derived from the Dutch.

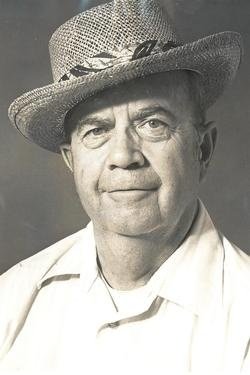

When I first arrived on the scene, Garth Muchmore (a good Scottish name, both first and last) the publisher of the newspaper, packed a revolver when he carried the weekly payroll in cash from Security Bank three blocks down 3rd Street every Wednesday. And he always wore a 3X Beaver Stetson cowboy hat. Nobody fucked with him. This is as far as I went in journalism, and I documented nearly every aspect of life in that prairie town with a camera, using Tri-X film.

Carl and Esther Coates were salt of the earth. That sounds cliché, yet cliches often persist because there’s an element of truth in them.

In that bygone era of grade school, when a collection of students was together in the same room with the same teacher for an academic year, my sixth-grade teacher bought us all a smart looking paperback copy of Roget’s Thesaurus. If he had handed me a bag of gold, it would not have been as valuable as that 50-cent thesaurus. It changed my life.

For high school graduation, my mother presented me with a portable manual typewriter and a hardbound copy of Roget’s Thesaurus. I’ve had a half-century relationship with that edition – longer than my connection with any one person, and it has accompanied me from St. Louis-to-Seoul, and all points in between. That edition from 1970 remains an integral part of my book collection.

Allegedly, Christopher Hitchens (1949-2011), an immensely talented wit and writer, could imbibe liberal quantities of alcoholic refreshments throughout the day, hold forth with ease and intellectual dexterity on literary, political and religious issues at both formal lectures and lively parties - then sit before a keyboard at 1 a.m. and produce a stunning essay for Vanity Fair that marked him as the rightful heir to Gore Vidal in his prime.

I’m still waiting for lightning to strike, to know what I want to be when I grow up, to be enraptured by a muse who will inspire me as much as June Mansfield (1902-1979) shaped the life of Henry Miller (1891-1980), her husband, who went unaccompanied to Paris in 1930 and during this down-and-out period wrote countless letters to his wife and friends in New York City that became the material for the scandalous Tropic of Cancer – banned as obscene for 30-years, edited by his mistress and benefactor, Anais Nin (1903-1977). Perhaps the best we can do is to be an interesting collection of contradictions.

Call me Kennedy. Ahab had his whale. William Burroughs (1914-1997) had his heroin. Bruce Chatwin (1940-1989) had his Patagonia. As for me, I have a camera and a passport.

The play’s the thing.

Michael Kennedy