My Promised Land: Xinjiang

Flowing Feast: Shache

The train ride from Kashgar to Shache took me just over an hour. It reminded me of an ancient legend that unfolded during the Tang Dynasty. At that time, the monk Xuanzang, in order to honor a promise, chose the land route instead of returning to Changan by ship. He traversed the treacherous Pamir Plateau, braving the harsh winds and snow, and overcoming numerous challenges to finally arrive in Shache.

In Xuanzang’s account, the Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, he vividly portrays the characteristics of this land: fertile soil, abundant agriculture, dense forests, and thriving flowers and fruits. The region boasts a diverse array of jade and enjoys a harmonious climate with gentle winds and rain. It was in Shache that Xuanzang dedicated himself to spreading the teachings of Buddhism, capturing the attention of countless believers and seekers. Although Shache had a population of only thirty thousand at that time, the temple located next to the city wall attracted an audience of ten thousand people daily, who eagerly listened to Xuanzang’s sermons.

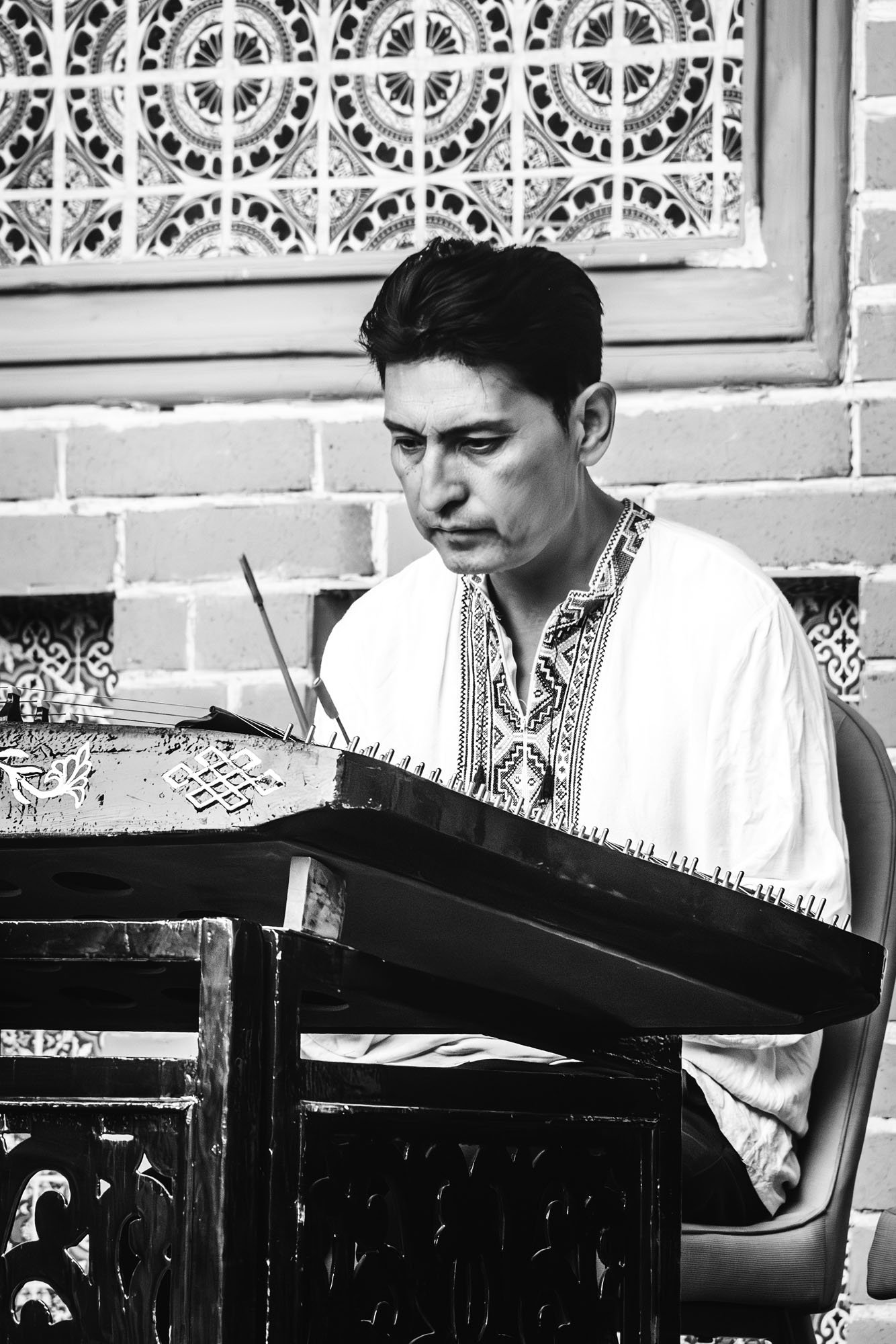

Strolling through the ancient alleys, I couldn’t help but notice the prominent depiction of a lotus flower, a symbol of holiness and enlightenment in Buddhism, adorning the mosques of Shache. From window frames to domes, this delicate artistic expression seamlessly blends the aesthetics of Buddhism with the architectural features of the mosque, showcasing the ancient culture’s diversity and tolerance. Furthermore, Shache is also the birthplace of the Twelve Muqams. When the melodious strings are played, it feels as though twelve radiant moons illuminate the depths of everyone’s hearts. The muqam music connects people closely, transcending the boundaries of time, space, and culture.

Amannisahan

The river, silently flowing through the expansive desert, displayed meandering and undulating curves reminiscent of a dancer gracefully moving amidst the sand. Known as the Yarkand River, it symbolizes life—a natural gift bestowed upon this land.

Meanwhile, a young girl tenderly plucked at the tanbur, creating a joyous melody akin to the bubbling of spring water. She became the embodiment of muqam's enchantment, singing a celestial and melodious tune. Like a luminous moon casting a gentle glow across the night sky, her voice resounded throughout the land, captivating all who listened. The muqam, enriched by her presence, radiated an unmatched brilliance, becoming a source of pride and a definitive symbol for this region.

One night, the king unexpectedly encountered this captivating young girl. Her voice soared like a lark, exuding an irresistible charm. The king was overwhelmed by the innocence of her melodies and was enamored by her tranquil and angelic beauty. On that silent night, a tale of love began to unfold.

She entered the palace and became the king's wife. She devoted her life to the realm of muqam, where timeless music and art were celebrated. With her grace and determination, she became a pillar of traditions and culture surrounding the muqam. She shone like a precious jewel, illuminating the royal palace and bestowing eternal glory upon the land.

Her name was Amannisahan, an esteemed musician and poet of the Uyghur heritage in the 16th century. She played a crucial role as the organizer of the Twelve Muqams. In those days, while the muqam was popular in folklore, it lacked standardization and organization. Recognizing its significance, Amannisahan immersed herself in the folk traditions, exchanging knowledge with poets and singers, meticulously collecting and organizing the scattered musical works. The result of her efforts was the magnificent masterpiece of Uyghur classical music known as the "Twelve Muqams".

With devotion in my heart, I stood before the Memorial Mausoleum of Amannisahan in Shache, Xinjiang, and gazed up at the majestic dome that resembled a crown. This memorial mausoleum stands at a height of 22 meters, resting on a square base that measures 2 meters in height and 10 meters in width. Its entire structure is adorned in a creamy white hue, adorned with delicate blue flowers. Prominently placed at the center is the coffin of Amannisahan, whose remains were transferred from the ancient Yarkand Khanate's royal tomb. The inner walls of the mausoleum palace are embedded with the names of Twelve Muqams. Symbolically, the fourteen white steps reflect the significant moment when she entered the palace at the age of 14, while the twenty pillars represent the two decades she dedicated to organizing and standardizing the muqam.

As I observed the exterior walls, I discovered poems inscribed in both Uyghur and Chinese languages, composed by Amannisahan. She wrote, "Muqam is the music of the dawn of the world, the qanun accompanies the world in its marching song." Another verse expressed, "I have never forgotten you in my heart, I have loved you in my heart as long as I have lived." Yet another poem lamented, "Spring has come, but I have no lover or home, like a lark that has lost its flowers to stay in the dreary fall." She cautioned, "Do not talk freely of the secrets of your heart to a villain; he will open your secrets to all."

Her verses transported me to another era, evoking a sense of time reversing as she materialized before my eyes. Her poetry carries a range of emotions, from solemn and profound, to lively and stirring, as well as brimming with romantic sentiments and profound wisdom, all of which leave an indelible impression on readers.

Amannisahan spent twenty years of her life within the Yarkand Palace. However, her journey was not without challenges as she experienced several unfortunate miscarriages. In 1560, after enduring a difficult labor, Amannisahan tragically passed away at the tender age of 34. Towards the end of her life, Amannisahan penned these words: "I leave behind nothing but these books of poems and hundreds of worn-out reed pens, stored in a pen bag within my study. Through reed pens, I have chronicled my history and my deep attachment to my homeland. When I depart, I request that these reed pens be boiled in water, allowing the fragrant essence to cleanse my body so that their scent may forever soothe me."

After the death of Amannisahan, the king was consumed by sadness and wept day and night. In her honor, he penned a heartfelt poem:

“O morning breeze, carry the secrets of my heart, Convey to my beloved my greetings,

Draw near to her at dawn or dusk,

And deliver my thoughts of deep affection.”

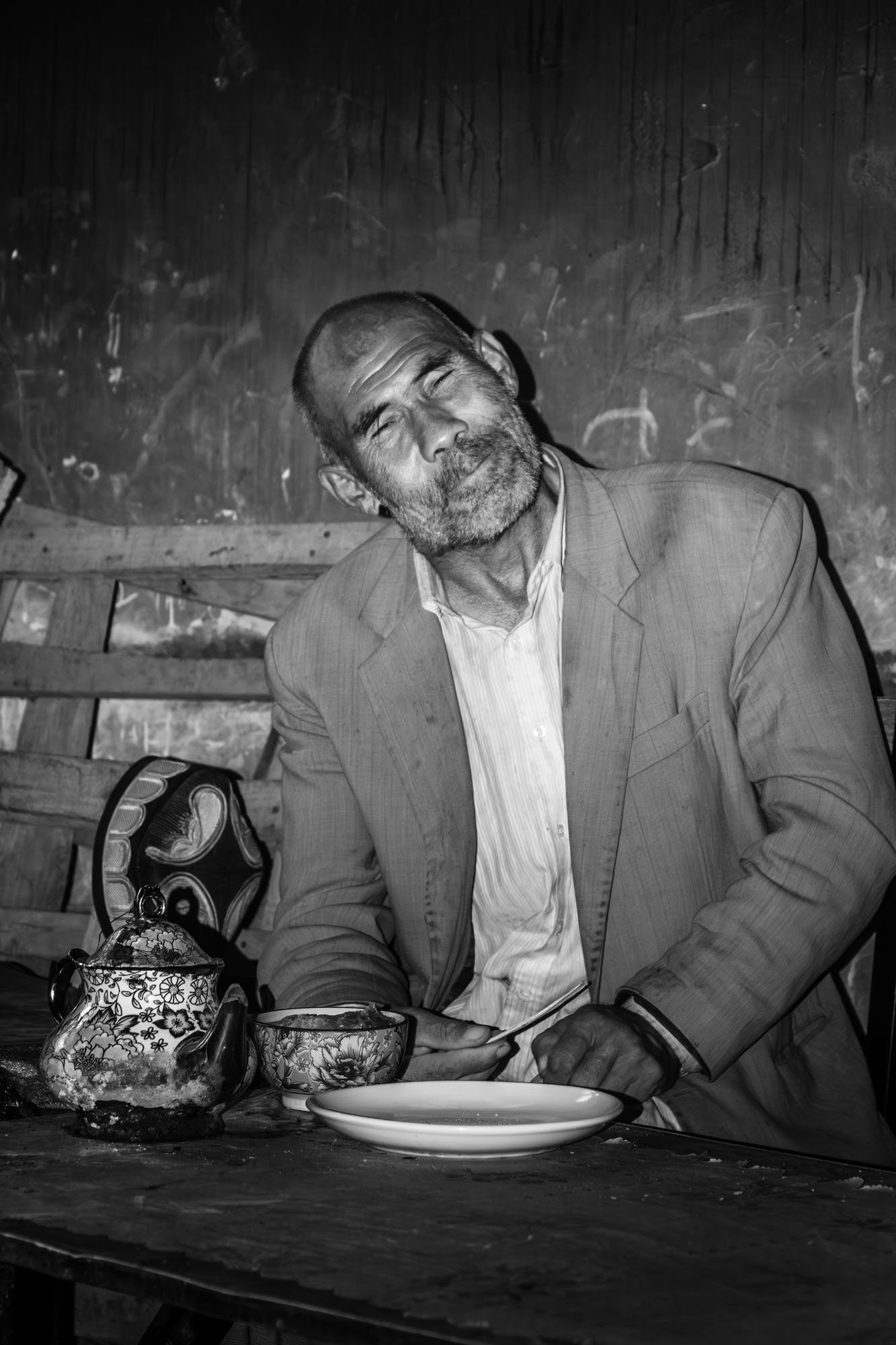

An Old Teahouse

The fruit trees lay still, each section neatly placed by the doorway wall. The faint woody aroma wafts out, reminiscent of the fresh scents found in a summer forest. In this small and modest space, there is no cool breeze or air conditioning to be found. Only the crackling firewood brings warmth, its dancing embers creating melodic notes that echo through the air, like wooden strings vibrating in every corner. The radiant glow, akin to the lingering dusk, gracefully flickers and sways at the edges of the room, harmonizing with the blazing flames.

An old television set plays the Uyghur-language TV series "Romance of the Three Kingdoms". The eldest Uighur men sit at a modest dining table, quietly savoring their hot tea. Some chew on naan, while others gently scoop up fresh egg yolks with their spoons. Some break the naan into pieces and dip them into the tea, creating a unique flavor. The teahouse owner moves back and forth between the stove and the table, the slightest eye contact expressing a profound sense of attentiveness.

Approaching the warm and cheerful stove, which is adorned with an assortment of teapots. Each teapot boasts its own distinct shape and color, resembling miniature worlds that carry their own unique aroma. However, the walls of the teahouse have become darkened by years of firewood smoke, as if the passage of time has etched a peculiar picture on an ink-like canvas. It bears witness to the accumulation of years, the mottled memories, and the countless ordinary yet intricate stories that have unfolded within the teahouse's embrace. Since the teahouse owner isn't fluent in Mandarin, I gesture my order—a pot of tea, a piece of naan, and an egg.

The teahouse owner adds more wood to the stove, creating a roaring fire. Standing up, he lifts the lid of the pot, releasing a wave of heat. He ladles the boiling water into a basin to sterilize the teacups before pouring clean water from a bucket into the pot. With a rag wrapped around his right hand, he carefully removes a teacup from the basin, wiping it clean. He then takes an egg, grabs a pot of tea, and finally picks up a piece of naan from the table, making his way towards my seat.

The breakfast laid before me is hot and invigorating. I delicately pick up the spoon, tapping the top of the egg. As the clear-as-water whites gently sway inside, a trace of disappointment washes over me, for I am accustomed to fully cooked eggs. Just as I hesitate to take a bite, the teahouse owner promptly approaches my table, deftly replacing the uncooked egg with a thoroughly cooked one before serving it to me. My gaze lifts, inadvertently gliding across the clock—a reminder that its hands are set to Xinjiang time, which lags two hours behind Beijing time.

The teahouse owner remains busy each day, chopping wood, boiling water, and preparing tea. He runs this not-for-profit teahouse, where tea, naan, and eggs are offered for one yuan. His efforts create a cool and relaxed atmosphere, allowing people to savor the bitter taste of tea while experiencing a state of tranquility. Such a teahouse serves as a serene station, offering a quiet resting place. Time appears to stretch out within these walls, akin to an exquisitely crafted clock, displaying a unique gentleness and delicacy as it passes. This stands in stark contrast to the hurried pace of the outside world, providing people with a sense of tranquility and the importance of slowing down. Perhaps within this teahouse, the owner no longer feels lonely.

Weekend Bazaar

In Xinjiang, a popular traditional proverb circulates: "In the Bazaar, you can find everything except your parents." This concise yet profound saying encapsulates the timeless allure of the Bazaar. I hailed a cab to the Weekend Bazaar. The bazaar itself is a bustling stage, meticulously sectioned into various areas including a flea market, clothing section, food street, and dance floor. It functions not only as a hub of commercial activity but also as a haven for friends and families to convene. After traversing every nook and cranny of the bazaar, these groups converge and engage in heartfelt conversations. In an era when transportation and communication systems were less developed, farmers regularly journeyed to the bazaar, employing donkeys to carry their wares. They came not only to trade but also to relish in the flavorsome cuisine and revel in the captivating performances by local artists.

As I prepared to leave the bazaar, a spirited Uyghur grandfather in his eighties intercepted me. He wore glasses and a neat white shirt paired with black pants, emanating a cheerful aura. Using gestures and simple Mandarin, we were able to overcome the language barrier and communicate. With a gesture, the grandfather beckoned me to follow him to an impromptu dance floor created from barbed wire and a tarp. Despite our limited means of communication, he assured me that a professional band and dancers were on their way to provide us with a captivating performance. He also excitedly mentioned that a muqam would be included in the show. Filled with anticipation, I eagerly awaited this cultural spectacle. Soon enough, the band members entered the dance floor, adorned with traditional instruments like the rawap and dabu. Leading the way, the kind elder introduced us to each other, creating a sense of kinship among us as we shared in the joy of music and dance.

On the stage, a dancer gracefully took her place, her movements flowing like a captivating stream. As the dance progressed, she extended an invitation for others to join, gradually increasing the number of dancers. Starting with pairs, they formed groups of three or five, eventually uniting as a larger ensemble. The music's tempo guided the rhythm, transitioning from slow to fast, harmonizing with the dance's evolving mood as the dancers matched their steps to the beat. With joyful leaps and bounds, the dancers skillfully displayed their artistry. In their performances, they incorporated simple yet meaningful gestures from everyday life, such as adjusting hats, rolling up sleeves, and swaying skirts, bringing vitality to the entire spectacle.

As the band played soul-stirring music in the corner of the stage, the audience gathered around, filled with anticipation. Their enthusiasm echoed throughout the venue, with cheers and applause for the dancers, creating an exceptionally warm atmosphere. Harmonizing with the dance, backing singers accompanied them with their melodious voices. They sang familiar songs while improvising new lyrics, depicting the moment and expressing the harmonious and joyful mood of the people.

"May your countenance shine as brightly as the sun,

And let my sorrowful eyes shed tears once more.

Oh God, for the sake of love, I have turned to ashes,

To show Perhat and Majnun the true essence of love.

Even if I were to spend a hundred years in the sky achieving nothing, I would rather rest beneath a mere speck of stone, never to awaken.

Oh Sak, if Navoiy weeps long and hard at the gathering,

Then fill his cup with a potent draught to make him forget his sorrows."

I was welcomed onto the dance floor with passionate invitations, feeling the rhythm of the music deeply resonating within me, as if the pulse of nature itself was beating in harmony. My dance partners guided me with patience and enthusiasm, showcasing their dexterity. As the music's rhythm enveloped me, I seamlessly merged in and confidently danced with freedom on the floor.

It was a truly exhilarating moment. The music surged like waves, carrying us along the path of pleasure. The Twelve Muqams, with their unique integration into the daily lives of the Uyghur people, became an inseparable presence. During times of hardship and freedom, they chanted their spontaneous and natural songs while toiling in the vast river valleys and amidst mountains and forests. These expressions of song and dance, known as the muqam, served to dissolve sorrows and alleviate inner pains, whether amid labor, longing for companionship, or confronting adversity and grief.

Each note and beat resembles a string of radiant beads, shining brilliantly in the long river of history. The Twelve Muqams serve as a medium to narrate their stories and preserve their history. They transmit emotions and wisdom to future generations through the interplay of music, dance, poetry, and folklore. This magnificent and flowing artistic tapestry permeates the vast expanse of the Earth, unveiling the fluctuations and glories of life.